|

|||||||||||||||||

November 2009 Web Edition Issue #3 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mondo Cult Forum Blog News Mondo Girl Letters Photo Galleries Archives Back Issues Books Contact Us Features Film Index Interviews Legal Links Music Staff |

The Guillotine

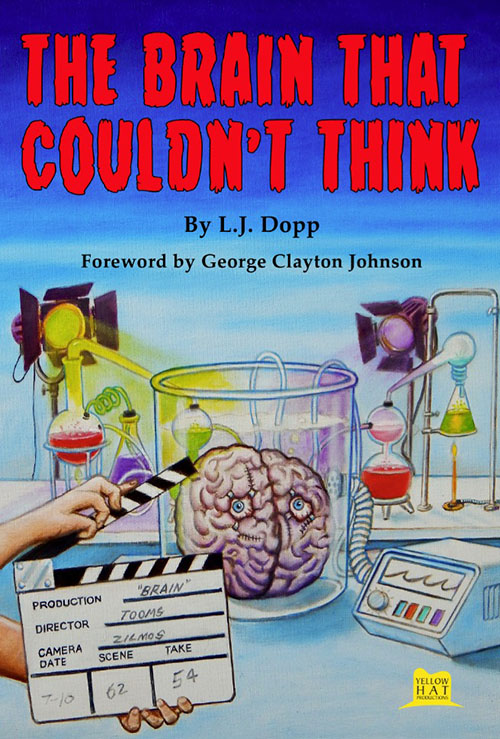

Brad Linaweaver ReviewsThe Brain

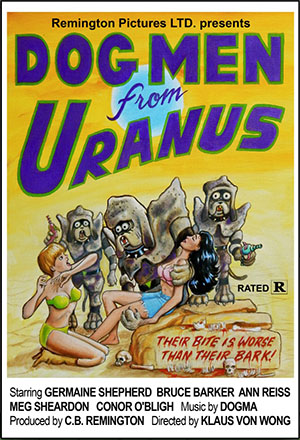

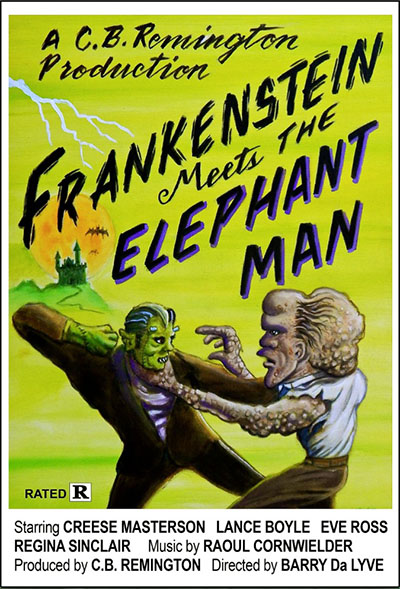

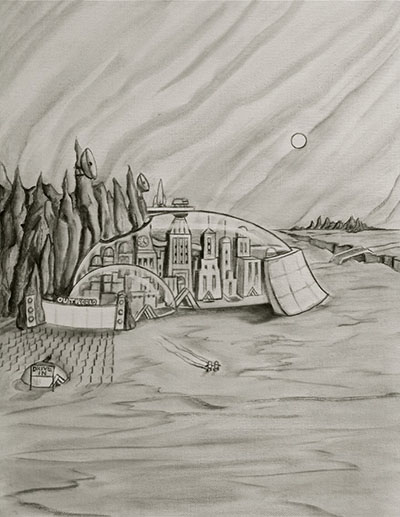

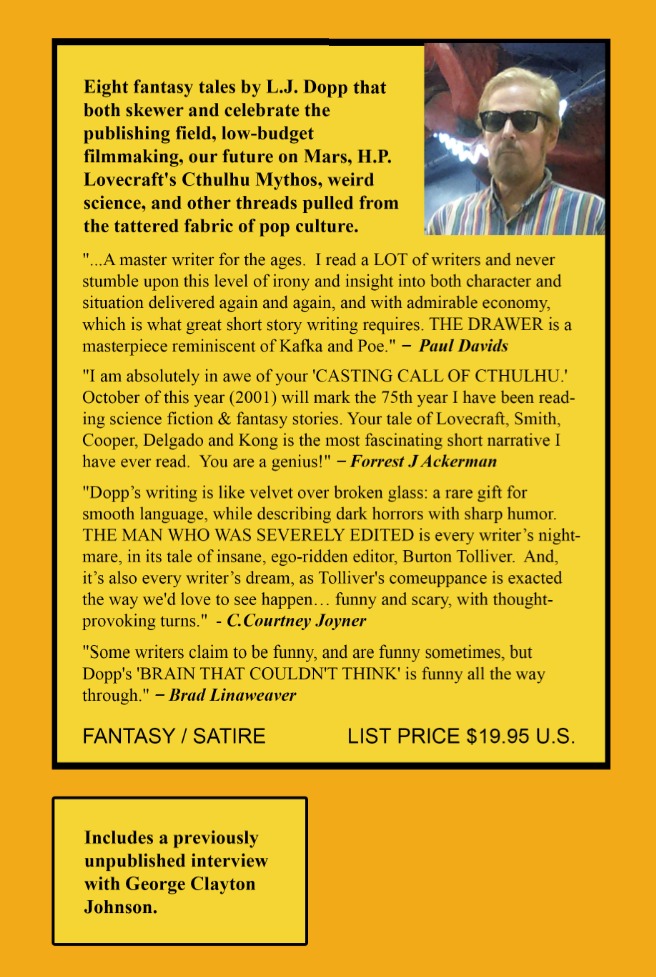

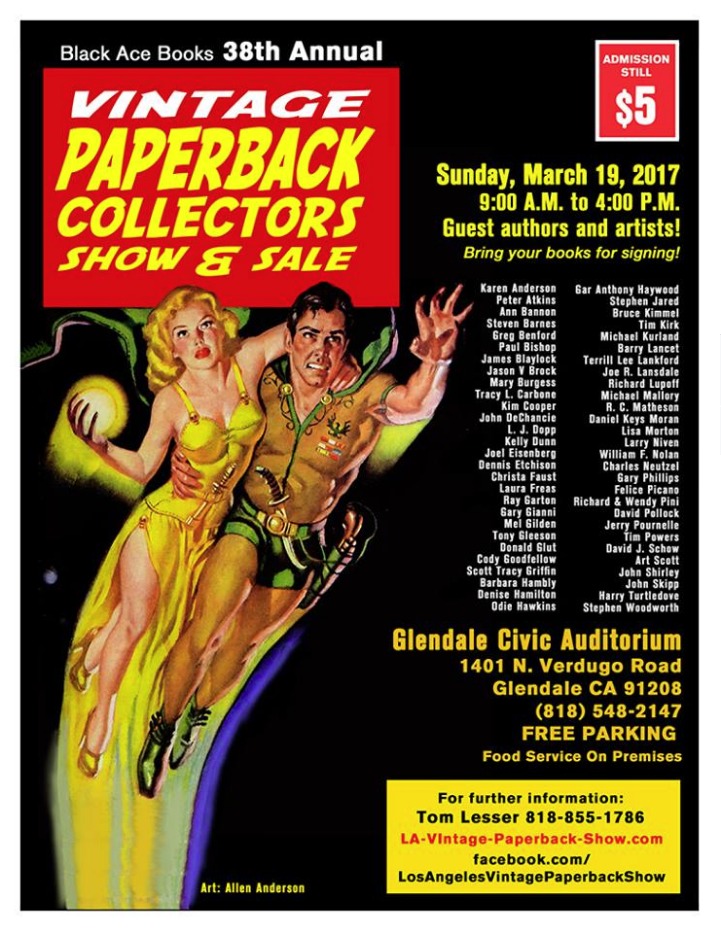

by L. J. DoppYellow Hat Productions, 2017 This book was a lifetime in the making. It contains multitudes. In the foreword, George Clayton Johnson promises that the reader will "discover what a fascination with pop-culture, a satirical turn of mind, an ironic sense of humor, and a head full of bright ideas can do to a man." He's introducing L. J. Dopp. One of the best short story collections in many years did not just happen. The thing had to grow over time, fed by the blood of cruel memories. You know the movies where the flying saucer lands? There is keen anticipation as nervous humans wait for something to come out. Suspense is an ache in the soul. Anything can happen. The Brain That Couldn't Think is a lot like that. Dopp has written fiction chock full of surprises. When's the last time there was a book of this kind? Many writers have become as predictable as a summer cold. Either trapped in the slowly grinding gears of genre conventions, or preaching a straight-jacketed ideology or theology, the only surprise is in guessing how long their next tome will be. These writers are so deep in terminal exhaustion that their work lacks the brevity of Charles Dickens. Dopp will have none of this. He does not sell escapism by the pound. He tells his story, and stops when it's over. As for his opinions, when he releases them from the dungeon and takes them out for a walk, they are well trained. Sure, they growl and pull at the clanking chains, but they know who's boss. That's because the writer under review follows the logic of a story to its inevitable conclusion, no matter how unsettling the result. There is no room for propaganda in brutally honest fiction. How refreshing to see a writer who only gets on his soap box at a comedy club doing business in the Twilight Zone. (Despite a fairly successful career as a short story writer, this reviewer has been guilty of letting Solemn Themes leave little yellow puddles on the street. Always appreciate seeing someone who avoids the problem.) So, who is L. J. Dopp? Where has he been all these years? Hollywood, that's where. There is no better place to wear a variety of multi-colored hats, slipping and sliding from one creative task to the next. The endless street is where the action is. We're not talking about a protected sliver of Tinsel Town, where the new French aristocrats -- the movie elite -- only deign to come near the rabble for awards ceremonies and film premieres. No, we are talking about the world of truly independent films, empty storefronts, unusual night clubs, naive tourists and cautious nostalgia. This is the shadowy world out of which many of the stories in this collection crawl, however briefly, into the light. Why have these admirable fictions, stretching over decades, not been in print before? One answer is simply a case of editors who didn't get the point. Their skill set wasn't wide enough to encompass the background of these stories. The brains of those who provided the typical rejection is best summed up by Bela Lugosi in the Monogram movie, Return of the Ape Man. In surveying a room full of unimaginative party goers, the mad scientist played by Lugosi dryly comments, "I enjoy studying people. You know, some people's brains would never be missed."  Even so, it's worth noting that it has required the publication of a whole book for these stories to finally reach an audience. Dopp's many careers reach an apotheosis in this collection. He directs and produces, illustrates and paints, does props and set design, and writes music -- bringing all these skills to bear in his 2012 co-production of The Boneyard Collection, a horror anthology feature hosted by Forrest J Ackerman. He's also been an actor, journalist, print art and advertising director; and, of course, he's written screenplays. Un-produced scripts haunt The Brain That Couldn't Think. The Hollywood writer, who really is a writer, stars in his own perpetual version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. By day, he endeavors to be one of the boys, a team player, and scriptwriter. But when the shadows fall, and raccoons bay at the moon (however that sounds), amidst the clattering of trash can lids, Mr. Hyde emerges. His fingers twitch, not in anticipation of murder, but ready to type short stories, novellas, novels. The results are so damned funny that the reader should strap himself to a chair, lest he do himself an injury when levity meets gravity. For example, the title story of the collection is not the first tale about a sleazy has-been producer trying for a comeback with a dodgy script. As for Curt Siodmak's well worn theme of a human brain kept alive outside the body, here we go again. However, please hold onto your heads, because this has to be the first time the brain is not that of a genius, or even an average person, but that of a retarded youth. You read right. In the full glory of political incorrectness, there is no more perfect metaphor for the endless series of wrong decisions made by Dopp's characters in these tales of thwarted ambitions. The first story in the collection is not about movies, but treads water in the same murky universe. "The Man Who Was Severely Edited" inspired C. Courtney Joyner to observe, "Dopp's writing is like velvet over broken glass." Here we have a writer/editor, not yet a has-been, but in the fast lane headed for POEtic justice. Yet another plagiarist, Burton Tolliver long ago misplaced the discriminating faculty. He can no longer maintain the high standards of his horror magazine, Dreaded Cutlets. No one is better at describing a burned out character than Dopp. Tolliver is so burned out that Smokey the Bear wouldn't care if an arsonist attempted to light a fire on the ashes. No spoilers in this review, except to say each story provides an opportunity for an afterword. They are worth the price of admission. "The Sound of Thunder -- the Wrath of God" is a love letter to Ray Bradbury. There can never be enough of them. The story is short and bittersweet. Someone with a sonorous voice should read it out loud, every Halloween.  Next, the reader must have a firm resolve with steady nerves to open "The Drawer." Along with "The Brain that Couldn't Think," the story carries an endorsement from this reviewer. Richard Matheson found the story gross and was actually revolted by it. Here is another opinion: "Has the power of vintage Weird Tales-era Ray Bradbury. The completely fantastic is made disturbingly real with images that will haunt you forever . . ." Matheson later told Dopp that he was glad his negative reaction had helped garner a good comment on the story. Paul Davids added another compliment with the insight that the story has the power of Kafka and Poe. There is no way, in heaven or hell, that any details of the story will be revealed here. Pay your shilling and see for yourself. The reader who survives rummaging through "The Drawer" deserves a fun trip to the movies. We're back at the novella, "The Brain that Couldn't Think," complete with illos for posters of movies made by C. B. Remington (formerly Bernie Small). Readers of Cult Movies, Worldly Remains and Mondo Cult would go to great lengths to see Frankenstein Meets the Elephant Man, The Brainmaker, Mono Lake Monsters and Dog Men from Uranus. We are at least spared posters for Corpse Eaters on Fire Island and The Last Vampire Movie II. But who wouldn't want to see the poster for Mommy Drunkest ? [All interior art is reproduced in black-and-white, the two color versions here are for our readers' enjoyment. - Ed.] This isn't the first story where a literal demon from Hell does business in Hollywood. Dopp simply pulls off the best version. Even though the demon has better ethics than several of the human characters, he fits right into the biz. This story also has the most satisfying writer's revenge ever, and a hostage situation that simply needs to be in a film, or on TV, or on YouTube (or somewhere other than the movie unspooling behind the reader's eyeballs). As we move to the next attraction on the midway, an appropriate soundtrack would be a newly discovered score by Max Steiner. This could be the best story. Let Forrest J Ackerman explain, from a letter (now blurb) to Mr. Dopp. "I am absolutely in awe of your CASTING CALL OF CTHULHU. October of this year (2001) will mark the 75th year I have been reading science fiction & fantasy stories. Your tale of Lovecraft, Smith, Cooper, Delgado and Kong is the most fascinating short narrative I have ever read. You are a genius!" L. J. Dopp notices things. He then asks the right "what if" questions.  H. P. Lovecraft wrote "The Call of Cthulhu" in 1927. The story was published in the February 1928 Weird Tales. The most influential piece in the HPL canon took a while to be widely noticed, and have a tremendous impact on the world long after his death. But it already had a small and loyal following by the early 1930s. "The Call of Cthulhu" could have been read by someone on the creative team putting together the project that became the movie classic King Kong in 1933. Points of similarity have to do with the discovery of an unknown island, architecture left over from a lost civilization, natives chanting in a pagan ritual, and a gigantic monstrosity from a pre-human world chasing sailors back to the sea. Therein the similarities end. But it's enough for Dopp's story to take flight on Pterodactyl wings. What if the similarities had been brought to Lovecraft's attention? That's enough to get started. What if there is also something to the Cthulhu cult? Better and better. Again we have the collision between the worlds of print and celluloid. There's nothing more terrifying than that. Moving on . . . . "The horror, the horror," to quote Conrad's Heart of Darkness, or Apocalypse Now for the film folk. Is there no escape from all this terror and torment? Well, actually there is a change of pace that is completely unexpected. Turns out that L. J. Dopp was such a fan of Robert A. Heinlein novels for teenagers (the juvies) that one fine day, he set himself down and wrote a pretty good space adventure about teenagers coming of age on Mars. Written for the sci-fi pulps but rejected, the resulting novella is so true to the spirit of Heinlein that our "Brain" writer could have had an entire career writing novels for BAEN. Dopp being Dopp, there are also illustrations -- giving the piece a strong flavor of short novel series like Victor Appleton II's New Tom Swift, Jr., Adventures; or Cory Rockwell's Tom Corbett, Space Cadet books. In the grand tradition, the title of the piece here is " Tommy Amos of Mars." This could easily have been expanded to novel length. The family unit is what it ought to be. The young hero isn't perfect, so he still has a lot to learn (from his girlfriend, especially). The villains are believable. The robot is the best character. The science is right. The plot makes sense.  From "Tommy Amos of Mars" Bradbury, the town where Tommy and his family live You get a lot for twenty bucks. All this, and more. More includes the next story, "Daughter of Depravity." Back to sex and blood. Female vampire author kidnapped by crazed fan. Back to Hollywood, in other words. Where's that ticket to Mars? Well, one of the domed Martian cities from "Tommy Amos of Mars" is referenced in the final, and wildest story. However, we're still earthbound in Hollywood. In fact, we're in two different Hollywoods, courtesy of time traveling aliens who have come to Earth with the malign purpose of changing Democrats into Republicans. That's funnier than it sounds. "In the Day" works like this. The Los Angeles Free Press, (The Freep), is thinly disguised as the L. A. Free Voice, (The Froice). Our heroes are good left-wing Hippies in 1972. They have their hands full with complications of free love and the threat of Nixon, or is it the other way around? Watergate is the flood zone, back then. That's not all that's wrong in Paradise. The Vulgarians -- the invading aliens -- are obsessed with Richard Nixon, as were we all, but they intend to use that particular leader of the free world to take it over. As for the Byzantine scheme, no summary can do it justice. The Bronson Caves provide the setting for a nicely icky Close Encounter. Every sci-fi fan will grok that. Speaking of which, references to Heinlein's The Puppet Masters, and also Invasion of the Body Snatchers, are done just right. Fotos abound. L. J. Dopp worked at The Freep in this period. His cartoon of Nixon doing the peace sign with one hand, while holding a rocket bomb (looks like a V2) with the other, was famous enough to land him on the White House enemies list. The striking image is reprinted for our edification. There's one more thing. The people from 1972 see what has happened to Hollywood in the early 21st Century. The real Hollywood, North and South, where people live in the real world, has been dying for a long time. More has been lost than a counter-culture of hippies and Head Shops. Everything is fading. The hell of it is that we didn't need an invasion of monsters from outer space to lose so much. Hollywood's last stand is a state of mind, as well as a piece of real estate. Perhaps one day the show biz elite will attend their Tuxedo and gown events on a sound stage made to look like the old town. Or it could be nothing more than special effects from an undisclosed location. That way the Glitterati may avoid the eventual revolution of Hollywood oddballs, the sort of mad dreamers celebrated in this book. Imagine a welcoming committee if the gods decide to return. There could be a dark red carpet leading up to a guillotine on the Boulevard of broken dreams. Imagine the infernal device dripping in genuine tinsel. Just a thought. The epilogue to The Brain That Couldn't Think is an interview with the Mind that could think, love, and create with integrity. Dopp's discussion with George Clayton Johnson sets everything to rights in a 5000-word, career-defining interview, which has appeared on several websites over the years (including this one) but never before in print. No matter how much a reader might believe he knows everything about writing, George knew more. We will not see his like again. This is a perfect way to end the book (which also includes an afterword by publisher, Paul Davids, and a brief author's biography). The Brain That Couldn't Think is available at this LINK.  Mr. Dopp will be premiering his book at the venue noted below:  | ||||||||||||||||