|

|||||||||||||||||

November 2009 Web Edition Issue #3 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mondo Cult Forum Blog News Mondo Girl Letters Photo Galleries Archives Back Issues Books Contact Us Features Film Index Interviews Legal Links Music Staff | TapestryRegarding the Incomparable Acting Career of

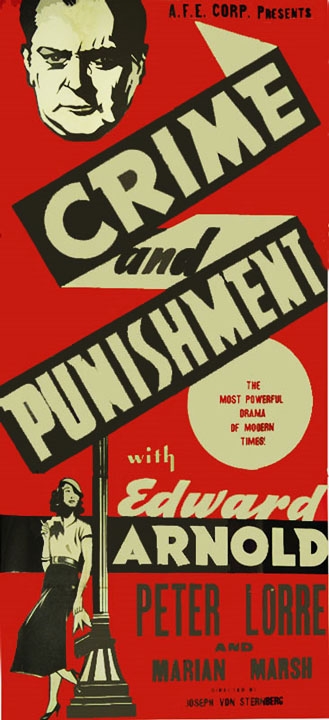

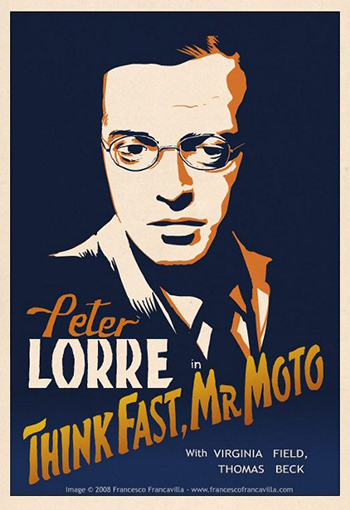

by Lucas ParisTo look at an actor or actress, requires one to look at the body of their work. An often exhausting process depending on how prolific the thespian, it is also quite often enjoyable as conclusions can be drawn from their successes and failures, making for contrasts or comparisons with other greats in the same field. Yet, there are actors that are singularly incomparable, with character that indelibly marked the industry. One such was Peter Lorre. Born Laszlo Lowenstein in 1904, the Hungarian Jewish actor’s story could be a film unto itself. Running away from home at a young age, learning the stage craft in Vienna before debuting in Zurich, working as a banker—then traveling throughout Europe doing stage in Germany, Austria and Switzerland before landing his first seminal role, a film role, in Fritz Lang’s revolutionary M in 1931. M, often cited as the foundation of the psychological thriller, shows a city in hysteria over a child murderer who has killed eight times without being apprehended.“The Mark Of M” is an essay by Stanley Kauffmann who states that the story of the film draws similarities from the Beggar's Opera by Bertolt Brecht (of whose works Lorre had acted in previously). It was this prior encounter with a familiar form of role that brought Lorre’s performance of the protagonist of the film to life. Lorre portrays Hans Beckert in the film, the child murderer who has turned Berlin against itself. The law, in its desperation to catch him, imposes upon every layer of Berlin’s society, culminating in a beautiful juxtaposition in the film where both police and underworld powers conspire separately to discover Beckert, and bring him to justice. Fritz Lang’s sensitive directing and nuance for story telling makes the struggle poignant and relevant, but it is Peter Lorre who brings sympathy and a reality to the inner turmoil of the tormented, monstrous central character he portrays. Lorre’s face is first seen in the film staring into a mirror, his lazy eyed reflection smug. He makes overt expressions into the mirror as a voice over of a pathologist describes his character’s madness through a sample of his hand writing that was sent to the press. Very theatrical in its way, Lorre’s acting here is loud, but necessary. Fritz Lang displays Beckert’s emoting through reflection again as he spots his next potential victim in a little girl via shop window. The series of emotions on display from Lorre can be easily understood without the aid of speech as dark desire, fed by uncontrollable impulses, surface. Once more, a reflection is used to reveal the M marked on his back by a beggar tracking him for the mob. Wild eyed fear and shock form; at once Hans Beckert is less a human and more of a frightened animal, a key trait Lorre likely carried over from his work with Brecht’s material. In one scene, the character of Beckert (after losing his intended victim when the child’s mother arrives) sits down at a restaurant table, smoking, rocking back and forth in his seat and whistling In The Hall Of The Mountain King sporadically between shots of cognac. Lorre does all of this seamlessly, giving us the portrait of man wrestling with an unbeatable monster inside him. The culmination of Hans Beckert’s character is shown when he is kneeling before a mob of the unlawful, a court held by criminals; captured, wretched and finally accused for what he has done. The breakdown of composure in the character as he shrieks his confession to his accusers (who are guilty unto themselves for their own crimes) is the pinnacle of the scene. It is also a moment of realization for the viewer. Hans Beckert, unlike the deplorable malefactors that condemn him, can’t help himself. There’s no reconciliation of his nature. He must kill. It’s a performance both believable and unnerving. Lorre’s Hans Beckert was so horrible to th public consciousness, that it collectively decided to throw rocks at him for the role. The German people stoned Peter Lorre over a performance. That depiction of Beckert’s psychosis, laid bare before peers, screaming of the horrors he’s committed, assured that if Peter Lorre never again saw a role on the silver screen, he would surely be immortal in film history for it today. But Lorre’s career does not end there. Leaving Germany early in 1933 (in light of Jews being restricted from film in the country after Hitler became cCancellor), Lorre found himself, along with his lover Celia Lovski, penniless and in Paris, after brief stays in Vienna and Czechoslovakia. Battling a then seven year addiction to morphine, Lorre ended up in the crosshairs of Alfred Hitchcock—and subsequently in 1934's The Man Who Knew Too Much.  This, another thriller, with its plot built around a kidnapping and clandestine assassination. It was a coming home to the familiar for Hitchcock—who had just had two flops in a row—and a salvation of sorts for a struggling Lorre. In the essay ‘Wish You Were Here’ by Farran Smith Nehme, Lorre’s Abbott is described as a terrific flip of his previous role as Hans Beckert. Where Beckert is an adult preying upon adolescence, Abbot is (emotionally) an adolescent preying upon adults. Perhaps this is further evidenced by the fact that when Lorre’s Abbott is first seen in the film he is accompanied by a nurse fussing over his health. Nehme also cites that Lorre learned his lines for the part phonetically due to his then rough English; the high, nasally vocalization would become Lorre’s signature trait originating with the part he played as the sinister, scarred and giggling Abbott. Be that as it may, Lorre is also notable in being one of only a few actors allowed to have his head on a Hitchcock set. Hitchcock, known for having a tight grip on all of his actors and their performances, loosened that grip for Lorre. Two unscripted moments in the film are entirely Lorre’s. One, is where Abbott (Lorre) hugs Nurse Agnes’s body when she dies in the epic gunfight at the end of the film. And earlier in the film, at Abbott’s hide-out “The Tabernacle of The Sun”, there is a moment where he comes up the stairs (where they are holding the protagonist of the film) after rebuffing the inquiries of a police officer, and finds one of his minions with a gun trained on him. Lorre playfully brings both of his hands high as if the recipient of a “stick up” after seeing the gun, he smiles and giggles. This, perhaps, further drives home the childish playfulness of the Abbott character, and is an illustration of Lorre being able to ad-lib in a way that fit his character. While the ad-lib is welcome and impressive, one still has to realize that Hitchcock didn’t allow such things typically, making one instance impressive—but two? That is shocking, and it illustrates a sense of trust that Hitchcock had in Lorre’s abilities; a trust he rarely placed elsewhere before or after.  The next outing for Lorre is an integral one—Crime And Punishment in 1935. This would be the very definition of a tour de force performance from Lorre as the complicated Roderick Raskolnikov; his full emotional range is on display as the impoverished, yet brilliant Raskolnikov. A just man in an unjust world where the authorities turn a blind eye to the misdemeanors of their men. Where a friend he finds in the beautiful Sonya (heartbreakingly gorgeous Marian Marsh) is fleeced by a ruthless pawnbroker before his eyes, only to be fleeced by the same pawnbroker himself moments later. She gives him a pittance for his father’s watch. And the final breaking point where his sister announces her impending marriage to a tyrant of a man. All of this sends Raskolnikov into a course of action that he cannot take back and with subsequent events that develop his moral and ethical conflict. Lorre generates this inner turmoil of Raskolnikov organically, showing the torn state of an honest man driven to the absurd extreme. One might observe, that where Lorre’s previous two roles were men who turned society on its head, creating chaos with their heinous actions, in Crime And Punishment, Lorre’s role is a man who has been thrown into chaos by the heinous actions of the society around him. He is not criminal—the environment he inhabits is. Going back to performance, after Raskolnikov (Lorre) murders the pawnbroker Leona, he is frightened, almost listless. Then, after seeming to have gotten away with his crime, he’s smug, confident, arrogant and even proud—as the ill act seems to bring rewards. Further, in a pivotal scene between Raskolnikov and Sonya, he is vulnerable, tender and feeling the tendrils of guilt creeping back into him. Irritability, anger and paranoia come next, when affable Inspector Porfiry (potently acted by Edward Arnold) begins dogging his steps. Lastly, acceptance, grief and fear again...culminating in a peaceful surrender that is as close to redemption that this character will find. Lorre’s virtuoso display through this is a rodomontade sleight of hand; a magician leading the eyes and tricking the hearts. Historically, Crime And Punishment is the unveiling of Lorre’s proverbial wares to the States and they would be bought. The “B’s” being lucrative in quantity, Lorre found a sustained stretch of work after leaving Columbia Pictures, by bringing JP Marquand’s Japanese Interpol Agent, Mr. Kentaro Moto, to life in Think Fast Mr. Moto (1937) for Fox. Despite reluctance to do the role, Lorre’s struggle with morphine would once more be an impetus that would lead to another memorable icon of the silver screen. A sad aside to acknowledge is that Lorre’s addiction was due in part to the common prescription of morphine in his time of prominence; a botched appendectomy, and a second surgery later would see to Lorre’s dependency throughout his prime years.

Characters from Asia, or “The Orient” being famous during the 1930s (sleuths namely) with Charlie Chan (Warner Oland) and Mr. Wong (Boris Karloff), Lorre’s eight stints as the international Japanese Gentleman of Mystery is not only timely but for them all, a bit of pioneering, as they predate what most would consider the archetype of the intriguing spelunker—Sean Connery's James Bond (Dr. No—1962). Also worthy of note, is that one of those eight Mr. Moto films was originally a Charlie Chan film (Mr. Moto’s Gamble, 1938) that had to be reworked with Lorre when Warner Oland walked off set, left the country for his native Sweden and died August 6th that same year. The film is shot for shot a Charlie Chan mystery, Keye Luke as Number One Son and all, but with Lorre’s Mr. Moto at the helm instead, giving it a darker resonance while making the film feel like a crossover of sorts. Regardless, Lorre felt trapped by the role and his success in it, not to mention personal as well as political reservations towards the role in the running up to WWII, given the Japanese atrocities in China at the time. Like many Bond actors, Lorre was often referred to as Moto on and off the set. That, and a sustained $10k rate per picture, and Lorre would eventually vacate Fox for higher pay. Still, he left behind a considerable body of work in those eight Mr. Moto B’s—from a slight, menacing smile in Think Fast Mr. Moto before ruthlessly ending an underworld tough, to genteel Judo lessons given to a young bellhop in Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation (1939), Lorre exemplified politeness, intelligence and refinement with Mr. Moto, while also embodying the American anxiety at the time towards the Japanese nation as a whole. Mr. Moto was good in that bad sort of way. The 40s saw further success and prominence as Lorre would find himself nestled between two industry greats in Humphrey Bogart and Sydney Greenstreet. With a role in Face Behind the Mask (1941), which could be debated as being an inspiration behind roughly half of Bob Kane’s villainous rogues gallery for Batman, and a practically scriptless but chilling acting job in Stranger On The Third Floor (1940), where Lorre’s eyes and taking off a hat make him one of the most unnerving monsters opening the decade. We arrive now, at The Maltese Falcon (1941). Put bluntly; Joel Cairo is a work of subtlety on Lorre’s part. While delivering uninterrupted lines, Lorre, with a single and simple act of an oral fixation on his prop, a cane, implies everything one needs know of his character’s sexual disposition—a disposition taboo to the era (and still is today, depending on your upbringing). Lorre would be paired opposite Bogart again in Casablanca (1942), a brief part as Ugarte; an anxious scum, in the film just long enough to set up the plot before being dragged off by the Nazis. Paired with Greenstreet, Lorre would cultivate a far more enjoyable, deeper chemistry than merely galvanizing the image of Hollywood’s tough guy, Bogart.  Joel Cairo Concurrent with Arsenic And Old Lace (1944), where Lorre plays a boozing plastic surgeon named Dr. Einstein, an interesting comedic piece for him as he looks so longingly at every bit of alcohol that passes by when he isn’t drowning himself in it, we see him in The Mask of Dimitrios as Cornelius Leyden. The character Lorre plays in this film is a Dutch mystery writer caught up in a case of a dead man, Dimitrios (who was a backstabbing malefactor dying under mysterious circumstances. Angela Lansbury would be in similar circumstances, decades later.). Fidgety, and somewhat timid, Lorre’s Leyden is a less dubious and more subdued, vulnerable creature then he typically portrays, especially in the face of Greenstreet’s enigmatic and spooky yet affable Mr. Peters. When the two first meet on a train, we see the difference in their respective demeanor. Then, in their second encounter, Peters ransacking Leyden’s hotel in Sophia with Leyden walking in on him, we are witness to a sort of magic. These two sharing a well scripted scene together; Lorre frenetic but oddly casual with a gun trained on him, and Greenstreet—flowing through his lines like free verse poetry, delivering as an orator at symposium would—in his questioning of Lorre. The fantasy that the viewer has been witness to for the last thirty minutes or so becomes reality in this moment, as Lorre and Greenstreet finally make the mystery of Dimitrios engrossing and meaningful. That is because the pairing is believable, with volatile qualities uniting explosively. It is this scene in the film that finally captures one’s imagination. Once Lorre and Greenstreet have it, there is little chance of walking away from the film thereafter. What is found in The Mask of Dimitrios is two great actors giving each other their best for the camera. The winner is the audience and film history. They (Lorre and Greenstreet) would pair off yet again in The Verdict (1946). Greenstreet plays Grodman, a superintendent of New Scotland Yard who loses his position when he sends an innocent man to the gallows for murder. The real mystery of the film begins when a murder occurs right across the street from Grodman’s residence. Lorre plays Victor, a close friend of Grodman’s and a successful artist. Greenstreet is the straight man while Lorre plays a rather comedic role; the two carry over a sense of camaraderie and familiarity from The Mask of Dimitrios. Of course, familiarity would not be surprising given they had worked together seven times prior. It lends credibility to the friendship they portray in the film. Ultimately, The Verdict is Greenstreet’s film, but Lorre’s levity and macabre expressions lend amusing asides, as well as disturbing ones. From a kiss on the bare shoulder of a dancer (he is doing up the back of her dress) to licking his thumb in the presence of others after firing a gun in self defense, Lorre is loud in the quietest of ways in The Verdict—and still unsettling despite not being the villain. The film’s twist ending should not be spoiled here, but one of the last lines spoken by Greenstreet’s character to Lorre’s character is “Goodbye Victor”. One can’t help but sense finality on the screen as well as real life. Looking back on these two films, a discovery quite shocking can be found. Lorre’s not the predator—Greenstreet is. Leyden and Victor are innocent, albeit somewhat neurotic characters, in contrast to Greenstreet’s Mr. Peters’ affable malice, and Grodman’s calculative, deductive and exacting coldness. Before moving into the next decade, The Beast With Five Fingers, also 1946, must be mentioned because it is not only uniquely fun to watch, but Lorre also seems to be having fun as Hilary Cummins. A nervous breakdown threatens him throughout the film, due to the appearance of the apparently disembodied hand of a dead, one handed pianist that proceeds to bump off cast members one by one. Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet in THE VERDICT (1946) Lorre isn’t phoning it in, but he seems almost a caricature of himself and his own acting. J. Carrol Naish does what he’s been known (and lauded) for, playing an exotic, foreign archetype, this time as an Italian in Ovidio Castanio. Another invaluable character actor for his time, to see Naish and Lorre together in a film makes Beast With Five Fingers a must see. Closing down the 40s, Lorre enters the 50s with Quicksand (1950) and a quick appearance in it as a scummy arcade owner opposite a panicky Mickey Rooney. The same decade would bring us Lorre’s personal outing in Der Verlorene (1951). Written, directed and acted by Lorre, it is evocative of M, with Lorre preying on women instead of children this time, as an ex-Nazi Scientist Karl Rothe, aka Karl Neumeister.  Peter Lorre as Hilary Cummins in THE BEAST WITH FIVE FINGERS (1946) Original Art by L.J. Dopp Likewise to being writer, director and actor, in the final part of the film, Lorre is judge, jury and executioner all in one upon himself. The film was not a success for Lorre, but Der Verlorene (The Lost One) feels as personal to watch as it likely was for Lorre to execute single handed. It is raw, moving and memorable. The only other real standout film for Lorre in the 50s would be 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954). Lorre’s image and character would precede him. Warner Brothers’ Mel Blanc and Paul Frees often imitated Lorre; Mel Blanc in Warner Brothers’ cartoon caricature of him and Paul Frees on a Spike Jones album with a cover of “My Old Flame”. Oddly enough, Lorre imitated Paul Frees imitating himself on the Spike Jones Radio Show, with Frees portraying him as more crazy than usual. (One is reminded of Andy Serkis coming back to Gollum for The Hobbit Trilogy and finding it hard not to imitate imitations of his own performance from the Lord Of The Rings Trilogy.) The sound of Lorre vocally is iconic, and has had many imitators. Lorre himself once stated that all one needed to imitate him was two soft boiled eggs and a bedroom voice. His voice, and sometimes likeness, have been used repetitively for decades after his death; look no further than Corpse Bride (2005) at a certain Maggot voiced by Enn Reitel. Going back to a drought in the 50s for Lorre, the 60s prove an interesting finale for the traveled, now sickly, actor. Voyage To The Bottom of The Sea (1961), might stand out as a final bright moment in an otherwise flickering career, but his work with fellow horror and thriller actor Vincent Price, is more notable as it brought Lorre back to familiar scenery. Tales of Terror (1962), saw Lorre as the wine drinking Montessor in the film’s “Black Cat” segment, opposite of Vincent Price’s Fortunato Luchresi. The wine tasting scene is comedic brilliance. But that is the unique quality to acknowledge here: Lorre is being funny, Vincent Price is being funny. The whole thing is funny. “The Black Cat” Segment in Roger Corman’s Tales of Terror is horror meeting absurd black comedy. It is at parts true to—and a send up of—The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allan Poe. But Corman, Lorre and Price weren’t done with Poe just yet. The Raven is such an amazing departure from the original Poe piece that it is hardly recognizable. Wizard duels, Boris Karloff, Lorre as a man turned into a Raven; there is more to laugh at than anything, but again we find ourselves acknowledging Lorre on a comedic plane rather than a morbid, scary one. Lorre had come back to horror as a jester, and it feels comfortable—and oddly natural—a final success, in black humor, for the tired actor.

Vincent Price and Peter Lorre in Roger Corman's TALES OF TERROR (1962) Tales of Terror (1963) would be the last strong outing from Lorre as Felix Gillie; again, Price, Karloff and Corman directing, make up the stage, and it is a fantastic final piece. While nuance isn’t on display, Lorre’s comedic quality shines through as a sympathetic, put upon sidekick to Price’s heartless Waldo Trumbull. (Lorre repeatedly messes this name up as Tremble.) Muscle Beach (1964), the considered swan song, need not apply as Lorre barely graced it. A stroke would take Lorre from the world, March 23rd 1964, his actual final screen appearance being in Jerry Lewis’ The Patsy, that same year. Price delivered the eulogy at the funeral. The writing, as they say, was on the wall; gaining roughly a hundred pounds going into the 60s, gallbladder problems and struggles with morphine led to the seminal actor’s much too soon death at age 59. Lorre’s story ends there, but his legacy lives on in the quietly loud incarnations of him that have followed. John Kricfalusi, creator of Ren and Stimpy (1991), cites Lorre as the inspiration for Ren. Listen—one can hear it clearly; the aforementioned Maggot in Corpse Bride; Flat Top’s vocal inspiration for The Dick Tracy Show (1961) and even the apparent tributes for Dr. N. Gin in the video game "Crash Bandicoot: Wrath of the Cortex" (2001), not to mention The Ceiling Fan in The Brave Little Toaster (1987). Influences abound, but are hard to pin down from there. One can see potential Lorre in Heath Ledger’s Joker, The Dark Knight (2008), when Ledger calmly, and creepily walks into a room full of gangsters, delivers several morbid jokes, then quickly dispatches a mob muscle in sudden, jarring violence. Something similar occurs in The Face Behind The Mask (1941). Even Gollum’s (Andy Serkis) interrogation scene in The Lord of The Rings: The Two Towers (2002) has a moment that feels distinctly pulled from M: Gollum; miserable and guilty of so much, is surrounded by accusers lacking any mercy. The emotional breakdown is hauntingly similar. Looking at the present imitating him, one can draw the conclusion that the contemporary has to contend with Lorre; not Lorre with the contemporary. As a sort of “Character Actor Zero” he pioneered the archetype by often being the prototype. He was a chameleon; blending his ability with others, such as Bogart, Greenstreet and finally Price. From M forward, regarding Lorre is that of regarding a tapestry, a well woven work of dramatic and comedic art: at once substantial, electric and profound. In the adolescence of film and Hollywood, Lorre is indispensable for his remarkable and amazing versatility. Watching his work through the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s, one finds that Lorre was in constant travel, playing a variety of parts despite his consistent work in the genre of horror—a genre that he would ultimately be remembered for. It is not enough to say that Lorre was a great actor, too many can be categorized as such. In retrospect, Lorre was a necessary actor, a crucial one that gave so much to the craft that he proves to be invaluable to the very fabric of cinema itself. Few actors can claim such a distinction and still be as subtly beneath the surface, as Lorre has become. The psychopaths we enjoy on screen, the scarred but affable villains, sympathetic creeps and frightening anti-heroes came from a foundation that Lorre helped lay down at the beginning. This is the Peter Lorre that must never be forgotten. Ever.

Lucas Paris being presented with the original work that helps to illustrate this article. Mondo Girl Vicki Marie Taylor does the deed at the Altamonte Mall Barnes & Noble in Altamonte Springs, FL. | ||||||||||||||||