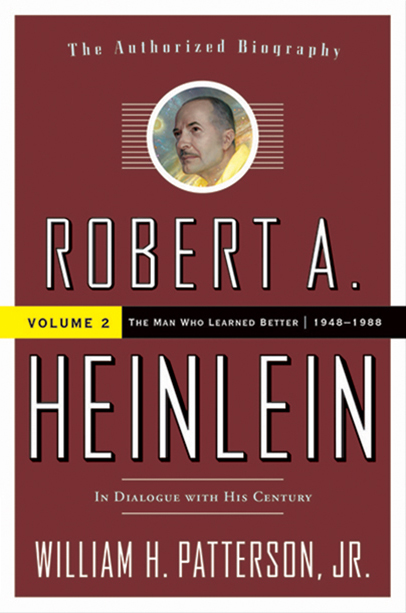

Welcome to the main course. Mr. Ritch took the opportunity to not only review Volume II of the Heinlein Biography by Patterson, but to discuss, in depth, much of Heinlein that is near and dear to his heart. Designing this epic essay for the web, so that it is easily read, has been a challenge.

And so, dear reader, we welcome you to a review in 7 acts. Just click on the rocketship at the bottom to continue on to the next section.

We are delighted to present:

Looking Back at the Sunset

by William Alan Ritch

Robert A. Heinlein—In Dialogue with His Century:

Volume 2: The Man who Learned Better

By William H. Patterson, Jr.

The second volume of William H. Patterson’s biography of Heinlein is a love story.

Primarily, it is the love story between Robert A. Heinlein and his wife Virginia Gerstenfeld Heinlein. It is also the story of Heinlein’s love for America; his love of liberty and the wide open spaces of the American frontier. It’s about his love of writing; his love of travel; and his love of mankind.

Once again, William Patterson has performed a Herculean effort in the process of creating this, the last volume of his Heinlein biography. Without actually asking him, I know that he found the theme for this volume during his reading and interviews. The theme is in the subtitle. Heinlein learned better.

There is the obvious surface level: as a man lives he learns better—but I am sure Patterson had more specific educations in mind. Heinlein improved the quality of his writing. He learned to market himself better. He learned how to stand up for what he believed. And in the very specific: he learned who to love.

It is strange that a love story begins with a wedding. That is of course how the previous volume ended: with Heinlein’s wedding to Virginia after their clandestine cohabitation.

Heinlein was trying to put the final, nightmare years of his marriage to Leslyn behind him. He was happy that she was trying to deal with her alcoholism by joining AA. But she was not destined to get any better. Instead, she continued drinking, and rather than moving on and away from Heinlein, she continued to libel and harass him from afar (only because he had moved half a country away from her). She wrote increasingly crazy letters to their mutual friends and acquaintances until no one thought Leslyn was sane.

Throughout, his Ginny was beside him. Their love grew through this—maybe even because of this.

Ginny was the partner that Leslyn never could be. It was the partnership of a full-time writer and spouse, who was his first reader, his biggest fan, and his most severe critic. In these partnerships it is the non-writing partner who must step in and handle the the day-to-day activities that take away from time to write. Mrs. Heinlein also took care of the fan mail (as it increased): answering the letters and keeping Robert away from the more annoying and persistent pests.

How did Ginny love Robert? She gave him the freedom of his personal choices about fidelity and nudity—despite what her actual opinions may have been. When he was in poor health, toward the end, she would sacrifice her own health to care for him—until Heinlein’s doctor lectured her about this kind of short-sighted “selflessness.”

Robert and Ginny Heinlein

Robert and Ginny Heinlein

How did Heinlein love Ginny? He used her as a role model for many of his heroic female characters. When she liked a story he knew he had a succeeded; when she didn’t, it was back to the typewriter. He bowed to her superior knowledge and intelligence. He moved away from a home that he had built and loved for her health.

In Patterson’s book we see the Heinleins working on books, fighting with the editors, looking for and moving into homes, dabbling in politics, taking up causes (such as nuclear preparedness, space exploration and blood drives), traveling the world, making friends all over and living long, full lives up until their deaths.

They were very private people. They did have friends and hosted social get-togethers but there was a clear separation between their public and private lives. Robert did not air his laundry, dirty or clean, in public. He disliked reviews that tried to psychoanalyze the writer. He disliked public disagreements—especially with his work in print, by his fellow writers. However, any subject was fair game—when writers met together to talk shop.

Patterson was personally chosen by Virginia Heinlein to create this biography. I am sure this biased Patterson a bit—but I am also sure that the portrait of Robert and Virginia’s life together is not a white-washed one. They were a couple where the whole was greater than the sum of their parts.

And that is a good definition of love.

This book is not an exposé. There is no attempt to find its subject’s feet of clay. There are no shocking revelations. Patterson is not writing a literary criticism. He is a biographer—not a critic. This is not a political discussion. Heinlein’s politics are discussed but there is no attempt to condemn nor support. All-in-all there is very little speculation on the part of William Patterson. He tells us the facts and lets us make of them what we will. There is little here to damage Heinlein’s reputation, and that alone, has infuriated his critics. We discover he practiced what he preached and he meant what he said.

Robert A. Heinlein was a complex man; a man of many parts. In a word that is the highest praise that he would respect: he was an American.

|